Go to:

TOC

Prev

Next

|

Lymph Nodes with Specific Reaction Patterns

Mycobacteria |

Cat-scratch |

MAI |

AIDS |

Toxoplasmosis |

Sarcoid |

Metastasis

IN the previous section, we looked at benign normal lymph nodes and, in enlarged nodes, their non-specific reaction patterns of follicular and paracortical hyperplasia and sinus histiocytosis. In this section we will examine common specific reaction patterns that enable us to identify the cause of a lymph node's enlargement. We will also consider nodes that are big because they contain cancer that has metastasized from sources exogenous to the node.

|

| Granuloma with caseous necrosis |

Many of these reaction patterns include granulomas (granulomata to the classically trained), which are aggregates of histiocytes that appear epithelioid. Granulomatous inflammation occurs in the presence either of:

•

an irritant that the histiocytes cannot digest or

•

a T-cell mediated immune response.

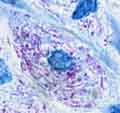

Granulomas in some diseases contain central necrosis, which may be surrounded by spindly histiocytes that "palisade" in a radial pattern; and, in turn, a cuff of small lymphocytes and plasma cells often surrounds the granulomas.

Another component of some granulomas are multi-nucleated giant cells composed of individual histiocytes that have fused.

|

| A foreign-body giant cell on the left; on the right a Langhans giant cell |

Their nuclei may be arranged wreathe-like around the cell periphery in Langhans giant cells or may be distributed more evenly in the cytoplasm in foreign body giant cells. Both types may be present in the same lesion.

Many specific reaction patterns (granulomatous or otherwise) are due to infections, in which case the etiology can be confirmed by culturing the infectious agent from nodal tissue or by staining paraffin sections to highlight the microorganism. Possible agents include bacteria, mycobacteria, spirochetes, fungi, parasites, and viruses. Non-infectious specific reaction patterns are seen in sarcoidosis, collagen vascular disease, silicosis, and dermatopathic lymphadenopathy (neither list approaches being exhaustive). Some of these diseases and their specific reaction patterns are considered in more detail below.

Mycobacteria

Lymphadenopathy due to mycobacterium tuberculosis is a prototypical granulomatous response (images). Classically such nodes are found in the pulmonary hilum or mediastinum draining a primary focus of tuberculosis in the lung. The granulomas include a kind of necrosis called "caseous", which appetizingly means "cheesy": the necrotic cells resemble, for example, putrid cottage cheese and lack the residual cell outlines perceptible in coagulative necrosis. Often calcification is present. Relatively uncommon these days, infection by M. bovis produces a similar picture.

In immunocompetent patients atypical mycobacteria such as M. avium-intracellulare(MAI) or M. kansasii also can cause a necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis (images). The last few decades have seen increased numbers of infections in childrens' cervical nodes caused by MAI or, less frequently, M. scrofulaceum. Some studies suggest that such infections can be distinguished from tubercular infection by the presence in the former of:

•irregular, serpentine granulomas

•ill-defined granulomas without palisading

•non-necrotizing, sarcoid-like granulomas

•neutrophils present in the necrosis

rather than scattered throughout the node

The subject, however, is controversial.

In the U.S.A. caseous granulomas lacking neutrophils are suggestive of mycobacterial infection or histoplasmosis . Definitive diagnosis requires either a positive culture or, a more sensitive but less specific technique, positive staining of bacilli in a lymph node section with an acid-fast stain such as the Ziehl-Neelsen stain. Caseous granulomas can be seen also in fungal infections; in these cases culture is more sensitive than tissue staining with a silver stain such as Gomori methenamine silver.

Mycobacterium Avium Intracellulare Complex

Histiocyte filled with acid-fast rods |

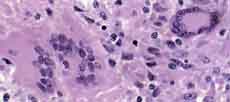

In immunodeficient patients (most commonly patients with AIDS) infection by this organism produces large aggregates of foamy histiocytes whose cytoplasm is stuffed with the acid-fast rods (images). This picture is different from the necrotizing granulomas described above, because the hosts lack the ability to mount an effective immune response. Sometimes especially in the extra-nodal gut, rod-stuffed histiocytes are found scattered singly in the tissue without any sign of inflammation.

AIDS

Lymph nodes play an important role in AIDS. During the long latent period when viral counts in the blood are minimal, the virus is replicating furiously within lymph nodes, relentlessly debilitating the immune system. Three stages are seen:

1) Early in the infection the nodes are "juicy", with florid follicular hyperplasia (images), monocytoid B-cell hyperplasia in the sinuses, and expansion of the interfollicular region by small and large lymphoid cells, plasma cells, vessels, eosinophils, and histiocytes. The follicles are often enormous and bizarrely shaped, sometimes with ill-defined mantle zones. In some cases bands of small lymphoid cells from the mantle zone break up the germinal centers, a phenomenon called "follicle lysis". An occasional citizen both within and among the follicles is a small multinucleated cell called a "Warthin-Finkeldey cell", also seen in measles.

2) Later (or sometimes at the same time as follicular hyperplasia) signs of follicular involution (images) appear. The follicles look small or "burnt out": for the most part only dendritic and endothelial cells populate the germinal centers, which appear naked without their mantle zones. Numerous plamsa cells, immunoblasts, histiocytes, and vessels occupy the interfollicular region.

3) Ultimately a lymphocyte depletion pattern may supervene, with follicles absent or memorialized by sclerotic scars. The lymphoid population is replaced by plasma cells and histiocytes.

At any stage the lymph node may be coinfected with several of the pathogens that opportunistically infect the patient with AIDS, such as mycobacteria, fungi, and others.

Cat-Scratch Disease

Truth in labeling: this entity is caused by a bacillus (B. henselae or B. quintana) found in cat paws and transmitted by scratching. Seldom a dangerous infection, it mostly effects nodes draining scratch-prone areas. The nodal response is characterized first by follicular hyperplasia and hyperplasia of the so-called "monocytoid B-cells" around the follicles and in the sinuses (images). Suppurative degenerative changes follow, often within or adjacent to the monocytoid B-cells. Eventually large, stellate granulomas are formed packed with cell debris and neutrophils. Late granulomas may show caseation. It has been said that one clue to distinguishing these from mycobacterial granulomas is that the latter usually show some mineralization, a feature they share with granulomas due to histoplasmosis.

With a Warthin-Starry stain small bacilli can sometimes be identified early in the process in capillary endothelial cells or histiocytes near the necrosis. Frankly, finding them amid the debris of your average silver stain is a nightmare, and they are also hard to culture. In some cases serologic tests may be helpful, especially if a history of assault by feline is given and studies for other causes of lymphadenopathy are negative. Most patients (60%) develop nothing more than a fever lasting several days to weeks and large, tender lymph nodes that may drain to the surface. In the unusual cases with systemic involvement usually recover without treatment, which is fortunate because antiobiotics are not very successful against the organism.

Cat-scratch disease most often affects axillary and cervical nodes. An identical histologic picture may be seen in inguinal lymph nodes infected by lymphogranuloma venereum.

Toxoplasmosis

T. gondii, the parastic agent of toxoplasmosis, is transmitted in most cases from cats--more exactly from kitty litter--or from ingested undercooked meat. Usually a harmless, inapparent infection ensues, but the results can be much more serious in pregnant women and immunocompromised patients.

Typically posterior cervical lymph nodes are enlarged unilaterally and show a classic triad (images):

•follicular hyperplasia

•monocytoid B-cell hyperplasia

•aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes

These aggregates encroach on the germinal centers and are not sufficiently well-formed or large to be deemed granulomas. Necrosis and multi-nucleated giant cells are absent.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidal lymph node |

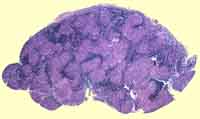

Sarcoidosis is an unexplained derangement of the immune system in which distinctive granulomas form in lymph nodes and other locations such as lungs, spleen, liver and elsewhere. Numerous strange phenomena accompany the condition, including peripheral blood CD4 lymphocyte depletion (the lymphocytes are accumulating preferentially in the affected tissues) and elevated serum levels of angiotensin converting enzyme. World-wide in its distribution, in the U.S. the disease afflicts blacks 15 times more often than whites. Though most patients do well, 10% die of their disease.

Pathologically, hilar lymphadenopathy is most common, with the nodes greatly expanded by non-necrotizing (well, a little central necrosis here and there is ok), small, well-defined granulomas (images). Called "naked," they lack the conspicuous cuff of lymphocytes seen in tubercular granulomas. Occasionally giant cells with cytoplasmic Schaumann's or asteroid bodies are seen.

Morphologically sarcoid is a diagnosis of exclusion. Even in the presence of typical, non-necrotizing granulomas, it would be a foolhardy pathologist who failed to order special stains for mycobacteria and fungi.

Metastatic Cancer

A harsh critic might opine that this is not a proper topic for a section on reactive lymph nodes, since "reactive" implies benign. So much for harsh critics! Carcinomas frequently metastasize to lymph nodes draining their primary location, so that axillary nodes may swell with metastatic breast carcinoma or neck nodes with metastatic oral carcinoma (image). Some nodes are notorious for being sentinels for certain malignancies: the left supraclavicular node ("Virchow's node"), for example, may enlarge as the first presentation of gastric carcinoma. Sarcomas, on the other hand, usually avoid lymphatic routes and spread via the blood stream.

Metastatic carcinoma in a node frequently induces fibrosis, making the node hard as a stone. And this is a good place to review the differences between benign reactive lymph nodes and lymph nodes with cancer, either primary lymphomas or metatstatic carcinomas:

|

Malignant Adenopathy |

Reactive Adenopathy |

|

•Matted |

•Freely movable beneath the skin |

|

•Non-tender |

•Tender |

|

•Stony hard if fibrosis is present |

•Less firm, sometimes fluctuant |

|

•Slowly, inexorably growing |

•Arising and subsiding over weeks or months |

Table of Contents |

Next section |

Previous section

|