Go to:

TOC

Prev

Next

|

Low

Grade Diffuse B-Cell Lymphomas: Small Lymphocytic and Others

Small lymphocytic | Plasmacytoid | Marginal zone | Mantle cell

THIS is a diverse group of lymphomas. The most

common and the prototypical type is small lymphocytic lymphoma

(SLL). The other types discussed here include:

- SLL with plasmacytoid differentiation

- lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (maltomas)

- mantle cell lymphomas

Mantle cell lymphomas are somewhat more aggressive than the

rest and probably belong somewhere on the spectrum between low and intermediate

grade. Besides these diffuse processes, additional low grade B-cell lymphomas with follicular differentiation are discussed in a subsequent section.

Taken as a whole, low grade lymphomas (diffuse and follicular, B-cell and T-cell) make up from 20-45% of lymphomas and have a median survival of 5 years or more. Patients are often left untreated until morbidity occurs. While combination chemotherapy usually secures a complete or partial response, the relapse rate is 10-15% per year thereafter.

Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma

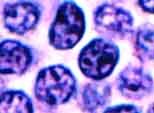

Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) (image) is almost identical to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) both morphologically and clinically. A somewhat arbitrary distinction is drawn between them based on the relative degree of marrow and nodal involvement and the numbers of circulating lymphoma cells. The normal counterpart of this lymphoma is a small subset of resting lymphocytes that are antigen-naive.

As a lymphoma, SLL acounts for about 4% of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. As a leukemia, CLL accounts for about 30% of adult leukemias in Western countries. In SLL the patients are elderly (median age 60 years) and usually present with diffuse lymphadenopathy and some degree of marrow and peripheral blood involvement (Stage IV disease). Mild to moderate splenomegaly is common. Constitutional ("B") symptoms are seen in 15%. Many patients have decreased normal antibodies (hypogammaglobulinemia) leading to infections. Patients may also have anemia or thrombocytopenia from marrow infiltration or more rarely from immune hemolysis. With the most sensitive techniques, a monoclonal serum immunoglobulin (M-component) can be identified in almost half the cases.

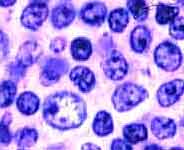

The larger cells are prolymphocytes / paraimmunoblasts |

In the lymph nodes, SLL shows sheets of small lymphoid cells that tend to flood the lymph node and its sinuses without destroying them and that usually respect the capsule. The cells have scant cytoplasm, rounded nuclei, darkly clumped chromatin, and inconspicuous nuclei. In isolation they are almost indistinguishable from benign small lymphocytes (Can you tell them apart?) Almost all cases of SLL include intermingled larger lymphoma cells with more open chromatin and more prominent nucleoli. These cells, called prolymphocytes or paraimmunoblasts, often occur in small islands called proliferation centers (image) surrounded by a sea of the smaller lymphoma cells. Proliferation centers must not be mistaken for follicles.

Because SLL/CLL cells have an unassuming appearance, minimal disease may be hard to detect, especially in the marrow. Immunophenotyping may help to identify it because the malignant cells usually express clonal kappa or lambda light chains. They also aberrantly express T-cell antigens CD5 and CD43, in addition to another characteristic antigen, CD23. Cytogenetically many cases show trisomy 12.

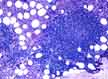

In the marrow, SLL/CLL (images) may be interstitial (scattered among normal marrow cells), diffuse, or nodular. The nodules are usually non-paratrabecular as opposed to deposits of follicular lymphoma, which love tightly to embrace the bony trabeculae.

In the marrow, SLL/CLL (images) may be interstitial (scattered among normal marrow cells), diffuse, or nodular. The nodules are usually non-paratrabecular as opposed to deposits of follicular lymphoma, which love tightly to embrace the bony trabeculae.

This lymphoma is very indolent but relentless, with median survivals of almost a decade. Although the slowly proliferating cells are sensitive to chemotherapeutic agents, chemotherapy is almost never curative and relapse inevitably follows. Most studies find no benefit in treating patients until they develop symptoms. Therapy tends to be low-intensity: single alkylator therapy such as chlorambucil or combination therapy with cyclophosphamide/vincristine/prednisone. A new and promising drug is fludarabine, but it has not been shown to prolong survival either. About 30% of cases of SLL progress to a higher grade process such as prolymphocytic lymphoma or diffuse large cell lymphoma (Richter's syndrome).

Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma, Plasmacytoid Type

Note the 2 plasma cells in the upper half.

|

SLL-plasmacytoid is an uncommon lymphoma affecting elderly patients. The patients often present with Stage IV disease; in fact initial involvement of the marrow, spleen, or liver is even more common than in SLL. Generalized lymphadenopathy is frequent, and the neoplastic cells circulate in the blood in about one-third of the cases.

Often the cells secrete IgM, and the condition is called "Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia." Bone involvement is almost always seen (images). The presence of quantities of this large protein in the blood may produce hyperviscosity symptoms such as bleeding, confusion, fatigue, and oncotic plasma volume expansion. For this and other reasons, survival is shorter than in SLL. About one-third of patients show evidence of hepatitis C infection. Though intriguing, this association has not been explained.

Against a background of neoplastic small lymphocytes, variable numbers of the lymphoma cells show differentiation toward plasma cells, either resembling them in appearance or like them containing monoclonal cytoplasmic immunoglobulin. It is this trait that distinguishes the lymphoma from SLL, in which the cells have surface immunoglobulin and may secrete it, but their cytoplasm does not harbor enough to detect with routine methods. The plasmacytoid cells may be sparse or numerous. In SLL-plasmacytoid some nuclei may contain PAS-positive inclusions called "Dutcher bodies". Other possible features include epithelioid histiocytes and in some cases residual normal germinal centers and open sinusoids.

Immunophenotypically this lymphoma resembles SLL. It is, however, more likely to be CD5 (-) and CD25 (+).

Marginal Zone Lymphomas (Nodal and Extra-Nodal)

Nomenclature is tough for these recently described lymphomas. In the REAL classification, marginal zone lymphoma includes both MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma, which by definition is extra-nodal, and nodal and extra-nodal monocytoid B-cell lymphomas. Most extra-nodal marginal zone lymphomas are epithelium-associated and best called MALT lymphomas (or more loosely MALTOMAs). Nodal marginal zone lymphomas may or may not include monoctyoid B-cells.

Nomenclature is tough for these recently described lymphomas. In the REAL classification, marginal zone lymphoma includes both MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma, which by definition is extra-nodal, and nodal and extra-nodal monocytoid B-cell lymphomas. Most extra-nodal marginal zone lymphomas are epithelium-associated and best called MALT lymphomas (or more loosely MALTOMAs). Nodal marginal zone lymphomas may or may not include monoctyoid B-cells.

All these various lymphomas usually display a variety of cell types, including small lymphocytes, monoctyoid B-cells, marginal zone cells, plasma cells, and infrequent larger cells. Occasionally a nodal pattern can be discerned, most often produced by residual benign germinal centers either surrounded or infiltrated by lymphoma cells. When the lymphomas occur near epithelium, they tend to invade it destructively to produce characteristic lympho-epithelial lesions.

The most interesting and probably most common entity in this category is the MALTOMA. These lymphomas (images) occur in many organs equipped with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue either as a normal component or as the result of chronic inflammation. Because the lymphoid cells have receptors that cause them to home selectively to their particular epithelial milieu, MALTOMAs have a remarkable tendency to remain localized without spreading to the marrow, liver, spleen, or blood. The patients, usually in their 50s and 60s, tend to present with localized, Stage I disease and have an excellent 80%-100% 5-year survival.

The most common site for MALTOMAs is the stomach, where they are associated with H pylori infection and a predominantly male population. Other MALTOMAs occurring in the lung, salivary gland, thryoid and other organs are associated with auto-immune disease (especially Sjorgren's syndrome)and a female population, but not with H pylori.

Treatment of gastric MALTOMAs in particular is a fascinating subject, because patients have apparently been cured by eradicating the H pylori infection with antibiotics. Such treatment may be acceptable first-line therapy as long as rapid tumor regression is not needed. Surgery (which is almost never used for the more systemic lymphomas unless the tumor mass is urgently symptomatic) and low-intensity chemotherapy have also been used satisfactorily.

Nodal marginal zone lymphomas are slightly more aggressive diseases compared to MALTOMAs, tending to present at a higher stage and having a 5-year survival rate of 50%. On the other hand, if compared to other diffuse, low-grade B-cell lymphomas, they present at lower stages.

Immunophenotypically marginal zone lymphoma cells express monoclonal surface immunoglobulin and pan-B-cell antigens. They are negative for CD5, CD10, CD23, and CD43. No chromosomal translocations are characteristic.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma (images) is distinguished from small lymphocytic lymphoma in several ways: Mantle cell lymphoma (images) is distinguished from small lymphocytic lymphoma in several ways:

- The cells have angulated nuclei instead of rounded ones.

- The infiltrate consists of monotonous sheets of small cells. In contrast to SLL, there are no prolymphocytes, paraimmunoblasts or proliferation centers. Unlike follicular center cell lymphomas, there are no large follicular center cells.

- There are often scattered histiocytes with eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm. These are neither tingible-body macrophages nor epithelioid histiocytes, although the distinction from the latter may be a fine one.

- Though usually diffuse, the low-power pattern is vaguely nodular in 30%-50% of cases. The nodularity may represent a selective infiltration and expansion of the mantle zones of pre-existing benign germinal centers by the lymphoma cells.

- Although like SLL the cells are reactive for CD5 and CD43, they are negative for CD23; and their surface immunoglobulin expression is significantly stronger as measured by flow cytometry.

- Clinically mantle cell lymphoma is a more aggressive disease. Average survival is 4 years rather than 8-9 years. Like SLL, however, it is resistant to curative chemotherapy because of the relatively low proliferation rate.

Mantle cell lymphoma has previously been called diffuse small-cleaved cell lymphoma. Sometimes it was and is called intermediate differentiation lymphoma or centrocytic lymphoma. Despite all these names, it is not common (2%-10% of all non-Hodgkin's lymphomas). It primarily afflicts elderly men, who almost always present with advanced, Stage III or IV disease and, almost half the time, with B symptoms. Extranodal involvement is relatively common, including:

- spleen, often massively involved.

- liver, usually in the portal areas.

- bone marrow (80% of cases), with a variety of infiltrative patterns.

- less frequently (10%-30% of cases) the peripheral blood.

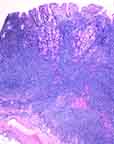

- less

frequently the GI tract (20% of cases). This may take the form of "multiple lymphomatous polyposis" (image) in elderly men. Numerous polyps are found anywhere below the gastroesophageal junction, with the ileocecal region most commonly involved. Within the polyp the infiltrate usually spares the mucosa, so lymphoepithelial lesions as seen in maltomas are not present. frequently the GI tract (20% of cases). This may take the form of "multiple lymphomatous polyposis" (image) in elderly men. Numerous polyps are found anywhere below the gastroesophageal junction, with the ileocecal region most commonly involved. Within the polyp the infiltrate usually spares the mucosa, so lymphoepithelial lesions as seen in maltomas are not present.

Over 75% of mantle cell lymphomas show a characteristic gene translocation not usually seen in other lymphomas: t(11;14). This rearranges the BCL-1 gene, also called CCND1 or PRAD-1, which codes for cyclin D1.

No satisfactory treatment is available. Neither low-intensity nor more aggressive chemotherapy produces median survival beyond 4 years or less. Autologous bone marrow transplantation has produced good response rates but not any definite improvement in overall survival.

Table of Contents |

Next section |

Previous section

|